The mobility landscape is fast evolving and companies have found it increasingly difficult to have only one policy covering all assignees. Over the past ten years, more and more employers have been segmenting their mobility policy, not just by assignment duration (e.g. long-term versus short-term) but also by expatriate assignment purpose (e.g. strategic assignment versus developmental moves or moves requested by the employees themselves).

Implementing a segmented mobility policy can increase the effectiveness of a mobility program but a segmentation approach needs to be aligned with business objectives and avoid unnecessary complexities. Here are tips to start off on the right foot.

Business Case for Policy Segmentation

The objectives of mobility policy segmentation are:

- Addressing the limitations of the one-size-fits-all types of policies.

- Reconciling talent management and reward / expatriate management: ensure that mobility policies and packages are better aligned with business objectives by determining the purpose of each assignment type and compensating them accordingly.

- Reconciling the cost control versus international expansion dilemma: increasingly employers face the challenge of having to contain expatriation costs while supporting the development of their global operations – in most cases by significantly increasing the number of international assignees. Companies need to find a way to channel their mobility budget from non-essential assignments to business critical ones.

- Presenting clear business cases / options to management to understand the cost and business implications of sending assignees.

- Managing effectively exceptions into a well-defined framework and process as opposed to ad hoc deals: the requirements of each assignee group is handled through assignment categories as opposed to one-to-one negotiation.

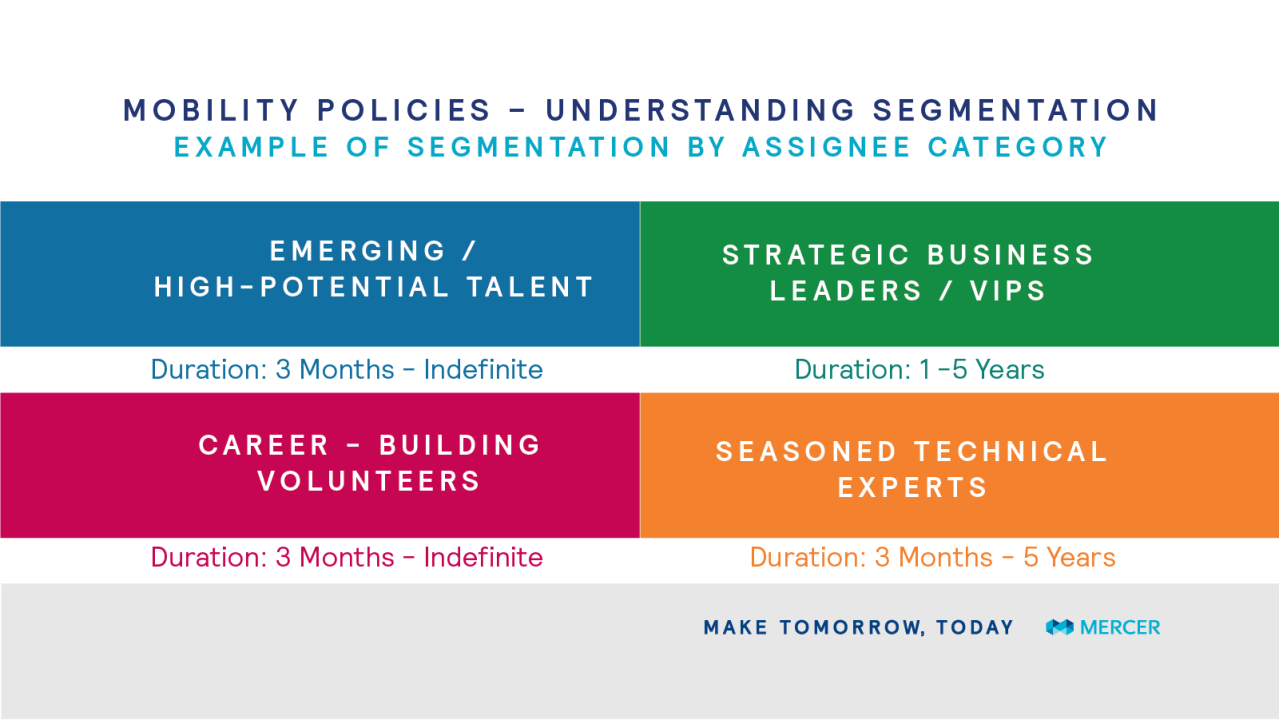

How to Segment a Policy by Assignment Purpose

Not all assignments have the same value for the business and for the assignees themselves.

- A first distinction can be made between assignments designed to fix business issues or address urgent skill gaps and those whose purpose is to develop high potential employees and future leaders.

- A second distinction can be made between business essential moves and those requested by employees for personal and career objectives. Companies should invest more in the business essential moves while providing only basic relocation assistance for retention purpose to moves initiated by the employees.

- Top level managers and global nomads with essential skills can have specific requirements and higher expectations than the average assignee. Furthermore, these VIP assignees are the ones who are most likely to request exceptions and who are the most likely to get them. For these reasons some companies create a category for these strategic assignees.

Other types of segmentation including geographic ones (regional versus global) as well as segmentation reflecting company-specific groups and organization setups are possible.

In practice, many international moves might have elements from different categories: e.g. an assignment to fix business issues might include elements of personal development and training. It’s important to clarify the main objectives of the assignments and classify moves as developmental; for example, only if there is a structured training program in place and clear learning opportunities.

The segmentation has to be based on objective criteria and not personal preferences. Some assignees might consider themselves to be “highly strategic” (or international) but in reality they are not. That’s why it is important to align segmentation with talent management and rely as much as possible on existing official talent categories within the organization to avoid individual negotiations. Mobility teams should rely on talent management teams to determine which people in the organization should populate their different segments.

Enabling Segmentation:

Introducing Flexibility into Expatriate Packages

Introducing a greater flexibility is possible by mixing different compensation approaches or by differentiating the content of the packages (allowances, premiums, and benefits) while retaining one main approach (e.g. the traditional balance sheet approach).

Companies are exploring various forms of local and local plus approaches. These approaches offer an alternative to the balance sheet approach for developmental moves and employee-requested moves.

At the allowance and benefit level, additional differentiation can be made. For example, incentives such as mobility premiums could be provided only to business essential moves. Similarly, the amount paid for allowances such as housing could be different depending on the type of move (i.e. having the company contribute to part of the costs for some moves instead of covering full housing cost). This differentiation should, however, be made bearing in mind the minimum requirements of all employees (minimum international standard) and the objective of removing barriers to mobility (i.e. not blocking the assignment).

Using Personas to Test Segmentation and Personalize Communication

We are witnessing a growing appetite for greater reward personalization within companies. This move in the directing of more personalization that goes beyond policy segmentation doesn’t imply creating more policies or revert to ad-hoc negotiations. Using typical assignee personas (e.g. the middle level manager with a family, the young millennial on a first assignment, the top executive etc.) can be a way to test how segmented policies address the need of different employee groups, help define targeted clear value propositions, and design communications for each of these groups.

Limits of Segmentation

Too much segmentation could kill segmentation. Bear in mind the following pitfalls before trying to go too far with your new segmented policies:

- Don’t segment for the wrong reason. Segmentation can help with cost control but don’t use segmentation purely for cost reasons. Reducing packages for an assignee category makes sense only if there are other incentives for these assignees; development moves could justify a lower package if there is a real career incentive to go on these assignments. Look beyond titles and jobs names, having different groups within the organization doesn’t mean that they all need to be treated differently.

- Keep it simple. It is tempting to go overboard with segmentation and multiply the number of categories. This can quickly become unmanageable. Using a decision tree helps organizations to determine the best approach. If there are ambiguities about categories or attempt from assignees or managers to negotiate categories, this could be a sign that the decision process is not clear or too complex.

- Experience shows that some categories are more relevant than others. Many companies have found that they have a need to differentiate between assignments for development purposes and the more traditional ones designed to fix business issues. On the contrary, when using the four quadrant models, some companies struggle with the distinction between standard assignments for technical experts and strategic ones. The difficulty is to separate the two types and also to make a differentiation between packages, i.e. if a company already provides a comprehensive mobility packages using on home-based approach for technical experts, is there a need to provide a higher package for strategic moves? If not, is it really useful to make a differentiation between the two categories?

Tips for Successful Implementation of Segmented Policies

There are several things you should do to help ensure the success of the new segmented policy:

- Don’t underestimate the impact of your company’s unique culture, history, and employee perception and mentality and avoid trying to replicate what others are doing. While the four quadrant model has been frequently used, many companies are using only three of two of the categories.

- Prioritize the change areas and phase implementation. It could take between four and five months to define the concepts and prepare the policy, another six months to start to implement it, and 18 months for it to be fully operational. So when you embark on a segmentation strategy, manage people’s expectations by making it clear that it won’t happen straight away.

- Gain support from the talent management team and seek approval of key principles by top management early in the process.

- Set a clear transition plan and process; the new policy would be applied to new assignees. Buy out (compensate) some assignees if they are resisting change.

- Establish a steering committee to manage the policy, track exceptions, and settle contentious issues. The danger of segmentation is that even if you gain approval for the core principles, after one or two years you could still have to start “negotiations” and the policy could start falling apart. Strong governance guards against this danger.